Creating Autism Friendly Spaces

Whether we’re in deep nature, landscaped parks, classrooms, clinics or our own homes, our surroundings affect us. Some environments unnerve, distract, or even endanger us. Other settings inspire and calm us. The spaces we occupy can make it harder or easier to focus, learn, and connect with other people. This is true for everyone—and especially so for autistic children and adults.

This guide reflects on the lived experience of autistic individuals as it has been shared with architects, designers, educators, and clinicians. It explores what researchers have learned from studying the effects of well-designed and poorly designed environments. And it includes the advice of experts who have created sensory friendly spaces, both outdoors and indoors, to welcome neurodivergent people.

We hope this guide inspires you and your colleagues to imagine, design, and build inclusive spaces for everyone in your community.

The ASPECTSS Framework

Autism friendly design starts with the input and participation of autistic folks. Magda Mostafa, PhD is Associate Professor of Architecture at the American University of Cairo; for over two decades, she has worked with autistic contributors to design and buildhealth facilities, campuses, and neighborhoods. She and her team developed the ASPECTSS framework to guide the design of projects for autistic children and adults.

Acoustics

When we audit our current spaces and design for the future, we can minimize noise distraction and echoes, especially in areas where high focus is needed. We can use sound absorbing materials on the walls, floors, and ceilings. We can create quieter zones and allow people to use noise-cancelling devices.

Spatial Sequencing

We can organize our environments, planning for a logical flow of people through the space according to scheduled sequences of events. We can plan quick access to quieter zones.

Escape

We can create easily accessible areas of very limited sensory input, where people can go to recover from sensory overload. We can design these escapes to be open, partitioned, or enclosed so people have options for different needs. We can use soft finishes and offer gentle movements, such as a porch swing might provide.

Compartmentalization

We can organize our spaces to provide discrete areas for specific purposes, adapting the sensory conditions of each area to the activities that will take place there. We can provide activity menus and maps so people know which activities take place where.

Transition Zones

At entry points, we can create sensory neutral areas that allow people to recalibrate as they move from high-sensory areas to lower-demand areas. We can use color, lighting, and materials to signal transitions.

Sensory Zones

We can organize our spaces so that areas of similar sensory intensity are close to each other.

Safety

We can keep the safety of users in mind as we develop spaces and select materials, recognizing that autism may affect the perception of sensory information and risk.

|

Something to Consider ASPECTSS is just one guide for design. What environments and events exhilarate you? What places seem to calm and ground you? What characteristics of each space make a difference? |

Research and Resources:

Mostafa, M. (2015). ASPECTSS: The autism design index. https://www.autism.archi/aspectss

Collaborative Design

Perhaps you’re designing a space that hasn’t yet been built. Perhaps you’re adapting an existing environment. Whatever the scope of your project, begin by listening to those in your world with lived experience. Neurodivergent people don’t all have the same sensory needs and don’t all encounter the same barriers. Taking the time to find out about the priorities of your students and clients will help you build trust as you build a space that works for everyone.

Interiors

To develop living spaces that meet the needs of neurodivergent children and adults, creators of the European SENSHOME project worked with autistic individuals and their caregivers to design interiors and furnishings with features that improved comfort, wellbeing, and safety, allowing residents to “live an easier everyday life” (Wohofsky et al., 2023).

“People on the autism spectrum and their caregivers were put at the center of the development process,” designers said. Throughout the project, architects focused “on listening as well as involving users and other experts in this field” (Wohofsky et al., 2023).

To learn more about specific skills, routines, and priorities, designers used a human-centered design process, holding 25 workshops with intended users. Users explained their characteristics, ranked their sensory and safety priorities, and described the features of interior environments that would make the most profound daily difference.

Following this research, a team of four designers, a psychotherapist, and five autistic teens met to design ideal living spaces for each teen. Participants used tools and material samples to create a basic plan, and then a 3D model, of their rooms. Designers said, “Their involvement has allowed them to identify the needs and desires for a space where they can live independently. It was an opportunity to observe how they live and what they would like their living space to be like.”

Designers used the workshops to create a SENSHOME system for broader use. Here's a brief look at some of the elements they included:

- tables with dividers to create separate sections for different uses and users

- semi-covered refuge armchairs to allow users to re-balance their senses or emotions without having to leave the room

- rooms with sound-absorbing materials that allow users to change acoustic conditions

- pictograms to facilitate lighting control and communication

- centralized visual agendas to make it easier to control the interior environment

Outdoors

In the fall of 2014, the Autism Nature Trail (ANT) existed only in the imaginations of its designers. They knew the autistic children in their lives responded to the waterfalls, woodlands, and canyons of Letchworth State Park in New York. But for many, navigating the vast park quickly became overwhelming. They needed to access that spectacular natural environment in a way that worked for them.

In making the ANT a reality, designers began by listening to the lived experiences of autistic visitors and their family members. Then they consulted with autistic experts locally and nationally, including acclaimed autism spokesperson Temple Grandin, PhD. Dr. Grandin advised the team to build the trail and design its programs in partnership with outdoor enthusiasts who were also autistic, or who worked directly with autistic individuals.

These guiding principles emerged from their collaboration:

- Locate the trail in “deep nature.” In her TEDx Buffalo talk, ANT co-founder Loren Penman shared Dr. Grandin’s advice: “Don’t build a strip mall nature trail, even though others are going to try to get you to move it to a city,” she said. Instead of adapting an urban or suburban location to make it more inclusive, ANT designers constructed an inclusive trail in the forest at Letchworth.

- Offer an orientation spot. It should be near the trail’s entrance so visitors can learn what’s to come and gradually adjust to the sights and sounds of the woodsy setting.

- Design the trail in a loop so visitors can see the endpoint from where they start. Being able to see where the trail ends increases a visitor’s sense of safety and security.

- Mark the trail clearly so visitors always know where they are. In addition to recognizable stone markers, the trail’s design team also used different trail surface materials to differentiate the main path from those that lead to its eight separate sensory stations. The main loop surface is stone dust, which makes the trail navigable by wheelchair. Other natural materials, including wood shavings, offer a different sensation underfoot, as well as a visual cue that you’re off the main loop.

- Incorporate choice throughout the experience. The ANT design team offered sensory, movement, and social challenges at each of the stations along the trail. They also provided opportunities to “opt out” of each experience. For example, visitors can explore natural elements like pinecones, pine needles, rocks, and leaves in a group setting, or they can handle the same natural objects in a solitary setting set slightly apart from the group space.

- Construct spaces where people can retreat and recover if sensory overload happens. Two examples: Gliders and cuddle cocoons offer a place to isolate and rock gently for those who may need a few minutes of solitude along the trail.

(Image used with permission)

The collaborative design of the Autism Nature Trail began with listening. The team expanded to include professionals trained in autism, speech–language pathology, physical therapy, developmental psychology, special education, occupational therapy, and other related fields.

Each advisory board member brought unique knowledge and experience. For example, Skott Jones, Ph. D, CCC-SLP created the Caregiver’s Guide to Facilitating Language on the ANT, and Keirsten Shaffer, NYS-LMT, CPT created an ANT Body Movement Guide. As a result, the one-mile trail can accommodate the needs of a wide range of visitors, including blind visitors and those who use wheelchairs.

As you design an inclusive space, whether you’re creating an indoor or outdoor experience, collaborate early in the process with those who have lived experience and those with specialized training in autism. Their expertise and priorities should shape the space as well as the programs that take place within it. Welcoming input from intended users is more than a simple rubber stamp of approval; it's a way to be proactive rather than adapting a space at the end of the process.

|

Here are two examples of helpful strategies from the ANT guides: Dr. Skott Jones writes, "For visitors with ASD who use language to communicate, try modeling simple sentence building scripts using a verb, descriptive, and noun (“I see a white bone….”, “I hear a loud woodpecker…”, “I feel fuzzy moss…”, “I smell fresh grass…”)." Keirsten Shaffer writes, "Choose body positions that fit your child’s needs while keeping them safe in their environment. The body positions in this guide are only a suggestion to get you started. Explore, explore, explore." |

Research and Resources:

Penman, L. (2022). A new path to inclusion. https://youtu.be/TFI2_2_PPG0?si=cUjqJrZ-44v_lOMR

Wohofsky, L., Marzi, A., Bettarello, F., Zaniboni, L., Lattacher, S. L., Limoncin, P., Dordolin, A., Dugaria, S., Caniato, M., Scavuzzo, G., Gasparella, A., & Krainer, D. (2023). Requirements of a supportive environment for people on the autism spectrum: A human-centered design story. Applied Sciences, 13(3), 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13031899

Predictability

Research and Resources:

Hamdan, S. Z., & Bennett, A. (2024). Autism-friendly healthcare: A narrative review of the literature. Cureus, 16(7), e64108. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.64108

MacLennan, K., Woolley, C., Andsensory, E., Heasman, B., Starns, J., George, B., & Manning, C. (2023). "It is a big spider web of things": Sensory experiences of autistic adults in public spaces. Autism in Adulthood: Challenges and Management, 5(4), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2022.0024

Wagenfeld, A., Sotelo, M., & Kamp, D. (2019). Designing an impactful sensory garden for children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. https://www.elsforautism.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Designing-an-Impactful-Sensory-Garden-for-Children-and-Youth-with-Autism-Spectrum-Disorder.pdf

Wiskera, E., Smith, A., Fletcher, T.S., Wilbur, L. & Chen, F.Y. (2024). Success on the Spectrum: Practical Strategies for Engaging Neurodiverse Audiences in Arts and Cultural Organizations. Rowman & Littlefield.

Choice

Sensory needs and autistic characteristics vary widely, so it’s important to consider where and when we can offer people options in what they experience. That way, visitors can co-create what they encounter in our shared spaces.

It’s equally important that our processes give people enough time to think about their choices with as little pressure as possible. This is especially impactful in places where sensory demands are high.

In one study exploring the needs of neurodivergent people in public places, an autistic adult said this of the pace in a local grocery store: “[I]t feels like, well, when I go shopping anyway, it feels like I'm being rushed or pushed into, you know, trying to finish tasks” (MacLennan et al., 2023).

Sensory Choices

Physical environments can be designed to support flexibility so people with different needs and preferences can choose what works for them. For example, when Ripley’s Aquarium in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina hosts sensory-friendly events, house lights are up and music is down or off. Those differences make it easier for autistic individuals to enjoy other sensory elements of the experience, such as the visual motion of sea creatures swimming by, without high contrast lighting or distracting sounds.

In one small 2024 study, researchers explored what happened when they provided motor skill interventions in multi-sensory rooms. Those spaces allowed children to calibrate “the frequency, intensity, and duration of sensory stimuli.” Adapting the sensory experience to each child’s needs led to fewer “defensive sensory behaviors” from sensory overload. Researchers suggested the customization could lead to more engagement and a better learning environment (De Domenico et al., 2024).

More research needs to be done to understand the potential benefits of choosing your own environmental characteristics in healthcare settings. In a study involving adaptive sensory environments (ASEs) in pre-operative settings, a group of autistic patients waited for surgery in rooms where the lighting, toys, seating, colors, and other features had been customized for them. Researchers measured anxiety levels and found that patients in ASEs felt less anxiety than patients in standard rooms. The results were statistically significant but were not dramatic enough to be considered clinically important, however. Researchers said they needed more information about which elements of the design were most impactful for their patients (Antosh et al., 2024).

Your Community’s Needs

An important step in designing autistic friendly spaces is closing the feedback loop. Suggestions from any general guide (such as this one) are only useful to the extent that they align with the needs and wishes of the people where you are.

Some organizations ask for feedback from guests as they are leaving the facility. The upside of that approach is that the experience is still fresh. The downside is that visitors may be at a low energy ebb when they’re on the way out. Some venues send follow-up emails or provide a QR code people can photograph as they exit. Others hold community workshops or send out surveys before and after events.

We can’t control every aspect of our environment all of the time. But it benefits everyone when we examine our processes and design our spaces to give ourselves and others as many choices as possible. Providing options shows that we value each person’s participation.

|

Something to consider Where are you most productive? Where do you seem to have the best conversations? If you could adjust one sensory characteristic in these locations, what would you change? |

Research and Resources:

Antosh, S., Drennan, C., Stolfi, A., Lawson, R., Huntley, E., McCullough-Roach, R., Hill, M., Adelekan, T., & Vachhrajani, S. (2024). Use of an adaptive sensory environment in patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the perioperative environment: A parallel, randomized controlled trial. Lancet Regional Health. Americas, 33, 100736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2024.100736

Clément, M. A., Lee, K., Park, M., Sinn, A., & Miyake, N. (2022). The need for sensory-friendly "zones": Learning from youth on the autism spectrum, their families, and autistic mentors using a participatory approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 883331. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.883331

De Domenico, C., Di Cara, M., Piccolo, A., Settimo, C., Leonardi, S., Giuffrè, G., De Cola, M. C., Cucinotta, F., Tripodi, E., Impallomeni, C., Quartarone, A., & Cucinotta, F. (2024). Exploring the usefulness of a multi-sensory environment on sensory behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(14), 4162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13144162

Jones, G. (2023, April 3). Experia researches sensory accessibility in sports facilities. https://www.experia.co.uk/blog/experia-news/sensory-accessibility-stadium-research/

MacLennan, K., Woolley, C., Emily@21andsensory, E., Heasman, B., Starns, J., George, B., & Manning, C. (2023). "It is a big spider web of things": Sensory experiences of autistic adults in public spaces. Autism in Adulthood: Challenges and Management, 5(4), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2022.0024

Tola, G., Talu, V., Congiu, T., Bain, P., & Lindert, J. (2021). Built environment design and people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063203

Sensory Considerations

Some people are sensory seekers. Sensory information must be intense for them to notice or feel it. They may look for ways to “turn up the volume” on their experiences. Other people are sensory avoiders—their sensory thresholds are lower, so they can tolerate less of certain stimuli. They may feel overwhelmed in situations where sights, sounds, smells, or the closeness of people are too much. Whether someone’s thresholds are low or high may depend on which sense is involved.

In environments serving autistic children and adults, it’s imperative that we pay attention to the amount and type of sensory stimulation in every area and each stage of a process. It may be helpful to conduct a sensory audit with neurodivergent members of your community, walking through your setting together and listening to feedback on what feels welcoming and what feels uncomfortable to different people.

|

Sensory experiences aren’t just a matter of personal preference. Ignoring sensory challenges can actually harm people. Sensory environments can impose barriers that prevent people from learning or from accessing the healthcare they need. |

In a study published in the British Medical Journal, 51% of autistic patients reported that these features of the waiting room kept them from readily seeking care:

Sound

In studies, sound is more likely to be problematic for an autistic individual than other senses. In a review of two longitudinal studies, researchers explored the conditions that made it harder for autistic children and teens to participate in public places. The participants talked about the sounds that caused them pain or deep distress.

One university student said:

Everybody is on their laptops typing at the speed of light and that tikatik noise, which drills into my ears to the point where I could not focus on anything the teacher was saying ‘cause all I could hear was the noise of the other students around typing, and I would have [panic] attacks. I would walk outside of the class because of that sound of people typing on their keyboards (Clément et al., 2022).

In large institutional settings, controlling acoustics can be challenging. Melissa Brito-Alvarez is manager of access programs at the Dallas Museum of Art. In a museum this size, with 4 floors and multiple galleries serving a large metropolitan area, sound can be a problem for autistic visitors.

“We still provide a sensory haven,” she explains. Museum signage and museum guides are on hand to show visitors to these havens. “We’re letting people know: ‘We know it’s busy. We know it's loud. But this is the space you would want to be if you want to escape all that.’ It's in our museum office floor.” In that quieter area, people can relax on couches and recover from louder galleries.

“For large events like spring break…we provide headphones and ear plugs because we acknowledge that adults also have sensory needs. Our music can get really loud during those public events,” Brito-Alvarez notes.

Sight

The way a space looks can affect how it feels to people visiting. Visual clutter and strong colors may distract, distress, or even cause pain for some autistic individuals. In her book Sensing the City: An Autistic Perspective, Dr. Sandra Beale-Ellis describes a challenge that sometimes arises when an autistic individual stays in a quaint B&B:

Smaller guest houses may be a better choice for some; they tend to be less busy, easier to find your way around and more peaceful. They are often interesting and quirky; many have small gardens or private sitting rooms for guests to relax in. One sensory challenge might be a tendency in some I have visited to fill rooms with bits and pieces which collect dust and can cause visual overload. This could cause a kind of motion sickness in autistic individuals.

Lighting can affect the sensory experience, too. Experts recommend natural lighting from diffuse sources. Clerestory windows and skylights may reduce the distraction that can come from windows at eye-level. Adjustable LED lighting is preferable to the glare and hum of fluorescent lights.

Touch

For those who are highly sensitive to touch, crowded or confined spaces can cause distress. Ceiling height can create a feeling of spaciousness that may be helpful. Unobstructed, clearly identified travel paths may also ease the sensory burden.

One autistic visitor explained how the arrangement of shelving saved him some anxiety in a favorite haunt: “I love going to bookshops. They tend to be quite quiet…particularly ones where the shelves are all quite spaced out from each other, so you're not kind of crammed in against other people” (MacLennan et al., 2023).

Smell

Cleaning chemicals, perfumes, out-gassing from furniture or building materials, fragrant vegetation, and other scents can keep people from participating fully in an experience or setting. Challenging odors can make it harder to focus, learn, and interact. Studies have shown they can also lead to physical difficulties such as these:

Indoor air quality, ventilation, functional air conditioning systems, and patterns of product use are important considerations (Zwilling & Levy, 2022).

Taste

Food and eating are part of the experience in many venues. It’s important to understand that food tastes and textures may be processed differently by some autistic people. Some researchers say between 70–80% of autistic children “engage in food selectivity” arising from their unique sensory experiences. These children aren’t simply “picky eaters.” Brain imaging studies show that for some people, there’s a relationship between certain brain structures and taste sensitivities (Goldschlager et al., 2025).

Communicating with prospective visitors about food choices may help them decide in advance how to handle eating opportunities.

Other Possibilities

In Sensing the City, Dr. Beale-Ellis extends her discussion of sensory differences to include these other realities for some autistic people:

- over- or under-responsiveness to temperature

- greater or lesser awareness of body positions (proprioception), which may affect the ability a person’s balance or sense of direction

- pain with common self-care tasks such as nail-trimming or wearing certain fabrics

- under-sensitivity to physical pain

- associating one sense with another, such as when a person sees colors when hearing certain sounds

- inability to tolerate certain food textures

- a need to move repeatedly for a while

- a desire to taste or touch certain textures or materials

These sensory experiences may bring comfort or cause distress, depending on the person and situation. Educating team members in your venue about these sensory perceptions can lessen stigma and prepare people to respond with understanding and kindness.

Dive into our infographic: How to Create a Sensory Friendly Classroom

Sensory Guides

(Image used with permission).

One way to communicate about the sensory experience at your venue is through sensory guides people can explore before they visit. A sensory guide explains the opportunities to engage each sense in different areas and ranks their intensity. For example, sensory guides on the website of the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum in St. Augustine, Florida provide these details of the experience:

- Maritime hammocks are generally quiet, with uneven or unpaved trails where low-hanging branches are present. The “touch” sense is ranked at a level 3 out of 10 on the maritime hammock trails.

- In the lighthouse keeper’s residence, sound is ranked 4 out of 10 because the enclosed space echoes and you’re likely to stand close to other visitors.

- Sound is ranked 8 out of 10 in the maritime center lab, where you may hear tools operating and museum employees speaking to groups of visitors.

- Touch reaches a 5 out of 10 within the lighthouse itself. That’s because the iron spiral stairs vibrate as you climb, humidity sometimes dampens the handrails, and it’s often windy at the top.

The St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum recently earned a Certified Autism Center™ (CAC) designation from the International Board of Credentialing and Continuing Education Standards (IBCCES). IBCCES offers several autism-related certifications to individual practitioners and educators, as well as to organizations and venues. These certifications require staff to be trained “to better understand what autism is (and isn’t), how to empathize and understand how autistic individuals experience the world, communicate more effectively, and be aware of common sensitivities and concerns in a recreational environment” (IBCCES, n.d.) IBCCES officials also visit sites to conduct sensory and safety evaluations, and the organization offers templates for resources such as sensory guides.

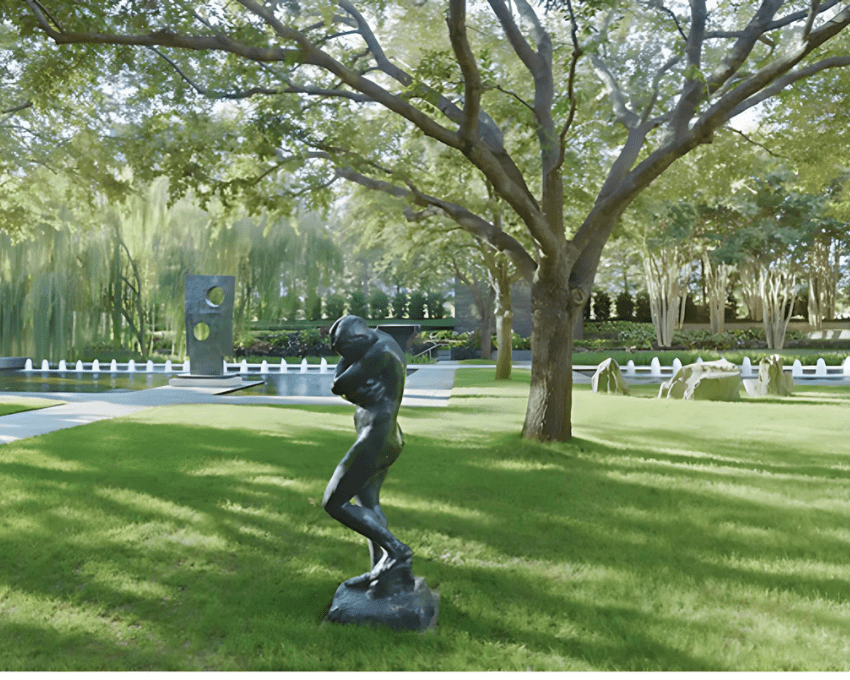

Regulation Tools

Some organizations offer kits or backpacks stocked with objects that can help people regulate their emotions in challenging social and sensory situations. Lynda Wilbur, senior manager of access and outreach at the Nasher Sculpture Center and co-author of Success on the Spectrum: Practical Strategies for Engaging Neurodiverse Audiences in Arts and Cultural Organizations, says visitors can check out “a backpack with headphones, a communication card, fidget, and a number of things that can help them regulate. We have those right at the front.”

Information about the backpacks is shared on the website so families know in advance what’s available on site. Reminders are posted throughout the museum. Wilbur adds, “Our staff has also been trained on how to interact if a child starts showing that their level of discomfort is rising. We can help them find a place that is more comforting to them.”

Sensory differences are part of the human experience. When we design with that natural variation in mind, our environments will be functional and inviting for more of the people in our communities.

Anna Smith, curator of education at Nasher Sculpture Center and co-author of Success on the Spectrum: Practical Strategies for Engaging Neurodiverse Audiences in Arts and Cultural Organizations, sums up the impact of the Center’s annual sensory days. She describes one family with a neurodivergent child whose birthday coincides with the sensory day in April.

“They treat it like her birthday party. She brings a hat, and her siblings come, and they bring their gifts for her. It's a safe environment where she can feel entertained and welcomed,” Smith says. The child feels as though the event is for her, and the family and staff have formed a special connection.

Research and Resources:

Beale-Ellis, S. (2017). Sensing the City: An Autistic Perspective. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, UK.

Brito-Avarez, Melissa. (personal interview, March 7, 2025).

Clément, M. A., Lee, K., Park, M., Sinn, A., & Miyake, N. (2022). The need for sensory-friendly "zones": Learning from youth on the autism spectrum, their families, and autistic mentors using a participatory approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 883331. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.883331

Doherty, M., Neilson, S., O'Sullivan, J., Carravallah, L., Johnson, M., Cullen, W., & Shaw, S. C. K. (2022). Barriers to healthcare and self-reported adverse outcomes for autistic adults: A cross-sectional study. British Medical Journal Open, 12(2), e056904. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056904

Goldschlager, J., Cintron, C., Hall, R., Shields, T., Tolbert, G.L., Woldebirhan, R., Agarwal, K. & Joseph, P.V. (2025). Taste processing in autism spectrum disorder: A translational scoping review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 170(106031) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106031

International Board of Credentialing and Continuing Education Services. (n.d.) What are the IBCCES certification requirements? https://ibcces.org/

Smith, Anna. (personal interview, March 7, 2025).

Wilbur, Lynda. (personal interview, March 7, 2025).

Zaniboni, L. & Toftum, J. (2023). Indoor environment perception of people with autism spectrum condition: A scoping review. Building and Environment, 243(110545). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110545

Zwilling, M., & Levy, B. R. (2022). How well environmental design is and can be suited to people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A natural language processing analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5037. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095037

Alone Zones

We all have limits to what we can tolerate. When social demands or sensory stimulation become overwhelming, a few minutes in a quiet setting can restore our equilibrium.

As we design and build spaces that welcome autistic people, it’s important to create and clearly mark places where people can separate from groups or highly stimulating areas to find serenity in solitude. Such spaces can be set apart by walls, vegetation, screens, partial or full fabric enclosures, or furnishings. To ensure safety, alone zones should have clear sightlines to other areas.

Escapes

Quiet retreat spaces do not have to be large. They do not have to be exquisitely decorated. In indoor spaces, a minimalist approach might be more useful to someone who is already experiencing sensory overload. Dimmable lighting, calm colors, and a variety of seating options are generally helpful—but discussions with the people you serve may shed more light on the specific elements needed in your setting.

Recalling her “meltdowns,” one autistic student wished, “If there was—if there was that opportunity to have a room that I could sit there, even if it’s just a tiny room where I could close the door and be with myself—it would drown out the sound a little bit” (Clément et al., 2022).

For many autistic individuals, the opportunity to be in a natural setting, or to interact with plants and animals, brings relief from built environments. One student described the sense of escape he experienced in a quiet music room his teacher made available:

I like it because my music teacher has a pet bird, two guinea pigs, and two rabbits. There are live animals. I love animals, and they make me feel calm. The room itself is quiet, except noises from the animals (Clément et al., 2022).

A courtyard, a sensory garden, a small seating area with a door or curtain to muffle sound. These intentional spaces allow people to regain their footing so they don’t have to leave the venue entirely.

Sensory Rooms

Sensory rooms for autistic children and adults have been used since the 1960s to help people regulate their emotions, enrich their sensory processing, and increase relaxation. Today, sensory rooms may offer experiences like these:

The specific contents and capabilities of a sensory room depend on practical considerations such as available space and budget.

In a study that extended over a period of ten years, researchers found that participating in a sensory room significantly improved the ability to engage in extra-curricular activities. Caregivers in the study said sensory rooms were very effective—more effective than conventional occupational therapies alone for improving sensory processing and motor skills (Awaida et al., 2024).

Virtual Reality

Virtual reality devices are sometimes included in sensory rooms. The devices are portable, and people can use them to access a vast array of immersive environments. Some devices offer hand controls that add touch sensations to the virtual experience.

Virtual reality experiences don’t work for everyone, but there’s some evidence that they may bring relief from anxiety and improve sensory processing issues for some autistic individuals. More research is needed to understand the effects fully (Mills et al., 2023).

Alone zones are most useful when visitors know such spaces are available and where to find them. It’s also important for staff to be trained in recognizing signs that someone may need a few moments to recover. A non-judgmental response can make a big difference.

|

Something to consider How could you find out more about what is and isn’t working for the neurodivergent people in your world? What form of collaboration would make sense given your team’s capacity and your community’s level of involvement? What’s one step you could take to begin? |

Invitation

We hope the stories and information in this guide will inspire you to create safe, sensory friendly spaces for the neurodivergent children and adults you serve.

For over 75 years, WPS has been working with educators and clinicians to develop and publish assessments for use in holistic evaluations. We invite you to explore our assessments, professional development, and continuing education opportunities related to autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other neurodevelopmental differences.

Research and Resources:

Awaida, I., Saleh, A. A., El Masri, J., Farhat, S., & El Tourjouman, O. (2024). Evaluating the efficacy of combining sensory room and conventional therapies for Lebanese children with autism: A 10-year study. Cureus, 16(9), e69953. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.69953

Clément, M. A., Lee, K., Park, M., Sinn, A., & Miyake, N. (2022). The need for sensory-friendly "zones": Learning from youth on the autism spectrum, their families, and autistic mentors using a participatory approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 883331. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.883331

Mills, C. J., Tracey, D., Kiddle, R., & Gorkin, R. (2023). Evaluating a virtual reality sensory room for adults with disabilities. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 495. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26100-6